Art is what is reflected by me everyday, everywhere, all of the time. Art is everything I do–sometimes in words, sometimes in sound, sometimes in pictures. Sometimes my art is little more than the process of thought. If what I do seems to reflect you and you find it difficult to forget, then it becomes a part of you and it is your art as well. This is when my art comes full circle and gains staying power.

THE INDEPENDENT

The Poet Spiel on life, love and dementia

Dying of the light

Published: January 16, 2018

Tom Taylor, 77, known also as Thoss W. Taylor or the Poet Spiel in his capacity as an artist, suffers from vascular dementia. The progressive and incurable disease will kill him, if something else doesn’t do it first.

It goes like this: Over time, blood stops making its way to parts of his brain, killing cells and, by doing so, damaging his capacity for reasoning, planning, judgment, memory and other cognitive functions. The brain breaks down — sometimes it happens quickly, and sometimes it’s a slower process. But eventually, Taylor will no longer be able to operate some critical part of his body. Then he will die. Those are the facts of his condition, clean and precise as the exam rooms where his doctors diagnosed him. But if that’s all there was to it, Taylor’s life would be very different than it is.

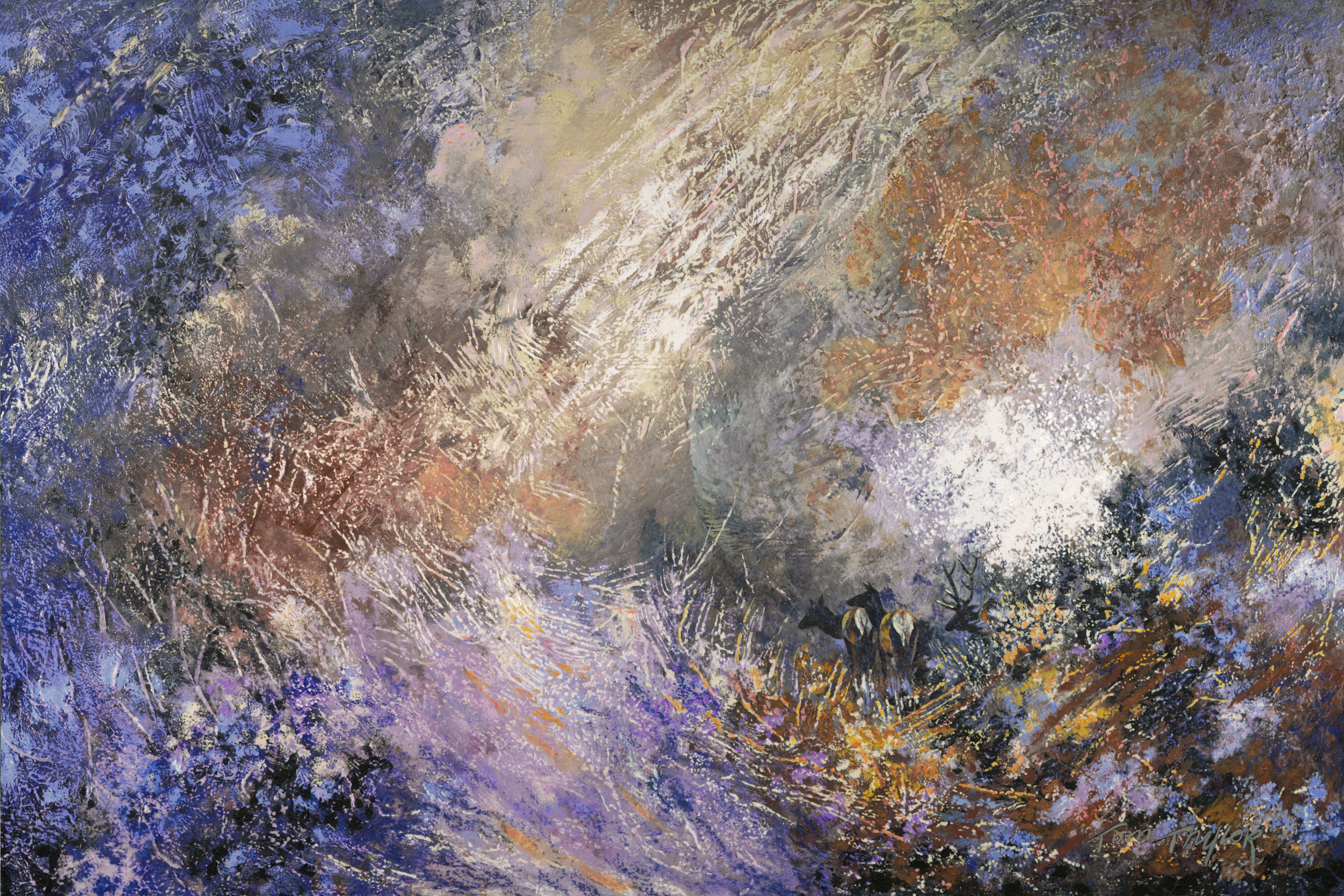

Taylor’s been an artist since childhood, boasting a career spanning decades. He’s shown around Colorado and across the country, and his wildlife paintings in particular have found display as far away as the Wildlife and Environmental Conservation Society of Zambia, in that nation’s capital, Lusaka. An elephant painting from 1985, called “Tuskers,” marked the height of his commercial appeal, appearing on mugs, teapots, sheets and more.

“His early work in the rendering of wild animals is rich in pattern and color,” says Jim Richerson, CEO of the Sangre de Cristo Arts & Conference Center. “His sense of design and implied movement in such pieces is very strong and lyrical.”

Taylor has utilized that skillset for more than just producing money-making work: He has also relied upon his art to cope with turmoil and trauma, both internal and external. He’s painted his pain and shared his own experiences living with bipolar depression.

“I’ve always jumped off cliffs and gone off and done something else,” he told the Indy in 2011. “I’ve never been an artist who’s stayed in one lane for long periods of time. Ever.”

Despite his illnesses, Taylor remains prolific as an artist. He lives with Paul Welch, his partner of some three decades, at his longtime Pueblo West home, where every wall hosts Taylor’s works, some decades old, some recent. Welch maintains an idyllic garden and goldfish pond in their backyard, fenced in by well-pruned junipers and trellises dotted with deep purple flowers, protected from the winds that whip across the surrounding flatlands. It’s a beloved oasis; they spend time soaking up sun when the weather allows, while Taylor enjoys a cigarette, or just a break from his creative work, best tackled in the morning hours, he says.

Because at some point every day, whatever he’s doing, Taylor’s mental function hits a wall. He has to sleep for a little while before he can get back to writing or making art. His body quits on him, limiting his output and capabilities, slowly silencing the once-prolific artist within.

If there’s a popular image of dementia, it has to do with short-term memory loss, and simple “senior moments” like leaving one’s dentures in the fridge. But to Taylor it’s more than what he terms “old timers’ disease.”

“I don’t want somebody out there reading this,” he says, “and going ‘Oh, I forget things, and this happens to me,’ and then they just brush it off, and they don’t understand the profound effect it’s having in my life and everything that I do.”

Dementia expresses itself differently in different people, but Taylor currently experiences a loss of motor function, manifested most clearly as clumsiness. He’s destroyed all of their good Pyrex dishes by thinking he’s set them down properly when he hasn’t; he says he doesn’t realize there’s something wrong until there’s a crash and a mess on the floor. His penmanship suffers, too, less than ideal for a man who’s been writing professionally for nearly two decades. Sometimes he can’t even read what he’s put to paper.

He also struggles with long-term memory loss. When he goes back to revisit his older work, especially the poetry and written work, it often feels like he’s reading it for the first time. On a long enough timeline, that sounds relatable for most writers. But it’s different for Taylor. The context of the piece doesn’t come back over the course of the reading. He loses the information for good, and nothing can bring it back.

“I have a visual in my head of these billions of little strings of [blood] vessels that go to my brain… and they’re suffocating and dying off,” he says. “I came up with the word ‘suffocating,’ I don’t know that I’ve ever read that, but that’s the way I see it.”

He first realized something was wrong while preparing for a retrospective of his work at Pueblo Community College’s San Juan Gallery in 2011. He and Welch, along with two of Taylor’s editors and two others, were helping set up selections of his art. “[There was] this unforgettable moment when all five of those faces were watching me with expectation, and I couldn’t remember who they were,” says Taylor, “and I’m thinking ‘Who are these people and why are they looking at me like this?'”

It took three months of cognitive tests, MRIs and waiting for his neurologist to offer the vascular dementia diagnosis, at which time, he was prescribed a drug called donepezil.

“I took it the first time, and I just all of a sudden felt fantastic and clear,” he says, noting that his responding so readily was the last step in confirming the diagnosis.

But donepezil won’t help forever. Taylor’s brain is still suffocating; the drug only slows the process. The decline doesn’t happen all at once. It worsens over a series of “step downs,” as Taylor and others describe them. When those happen, a whole swath of the “strings” he visualizes dies off, and he loses more brain function. He gets clumsier, and the words he’s trying to say don’t come to mind as easily.

“I am usually able to identify it with Paul and say ‘You know I just lost a whole bunch more brain,'” he says. Still, he’s holding up well enough seven years out from his diagnosis. He and Welch had discussions about selling their home and moving him into assisted living, but it hasn’t been necessary, and both hope Taylor will be able to live out the rest of his days there. “I’ve been in these kinds of situations before,” he says. “Yeah, I don’t like it, yeah, they’re unpleasant, but, hell, I’m used to dying.”

Taylor first wrestled with terminal illness in 1996, when he was hospitalized with crippling upper torso pain.

“My common bile duct was blocked 99 and nine-tenths percent,” he says. “Completely blocked. Nothing was passing through.” The doctors found a hole in his pancreas, a “fish eye.” He was preliminarily diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and told he probably had six months to live.

“When [the doctor] said it was cancer, I thought ‘I don’t know what that word means,'” Taylor recalls. “All of a sudden, it was about me, and I didn’t know what it meant.”

He was told he’d be going into surgery that afternoon but, in shock, he didn’t realize it was a biopsy to confirm the diagnosis. Taylor remembers holding Welch tight, thinking how he’d rather spend his last days with his partner than in a bed with tubes going in and out of him every which way.

He went about wrapping up his business affairs in between goodbye trips with Welch. In particular, he fondly remembers voyages to Yellowstone National Park and Cabo San Lucas.

“In Mexico, we got some Mexican weed, and I was on Percocet at the same time, just sort of floating around,” he recalls. “Every time I looked at Paul, I thought ‘I’m going to lose this, and he’s going to lose me too.'”

After that trip, Taylor got shocking news: His oncologist called to say he probably didn’t have cancer.

“Because there was no biopsy, eight gastroenterologists had had a meeting and then, based on whatever data they’d collected on me, had voted and said I had pancreatic cancer,” he says. “And I don’t know what made the switch back, but at some point, she said no, that’s not correct.”

The pain comes back sometimes, but the doctors now call it idiopathic chronic pancreatitis, with idiopathic meaning, roughly, “we don’t know why this is happening.” After two decades of treatments and surgeries, he still meets with his gastroenterologist regularly, and he’s been told pancreatitis will kill him more than a few times. Instead, it’s armored him against the prospect of death.

“Paul’s way of saying it… is I get to one of those places, and he says ‘we’ve been through this door before.’ That’s all he has to say to me. And I go at ease.”

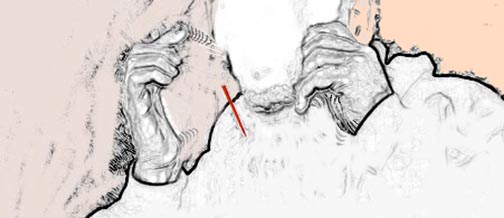

Though he faces his health challenges daily, Taylor refuses to stop making art and responding to the world around him. Recently, he worked on a sculptural piece called “Misappropriated Habitat,” exploring the places where human refuse has sullied what he says should be a place of comfort.

“What’s happening here, and I’m sure it’s happening in the Springs as well, is that there are just great caches of needles and paraphernalia that are found around,” he says. “I used bird nests [for the piece] — real bird nests — I used shattered glass, shooter bottles that were whiskey I think, some feathers.”

He set it all up in a cardboard box, something he’s enjoyed as a medium lately. It’s not acid-free or made to hold an image intact for decades to come, but he’s not so much concerned about that anymore.

Taylor says he also found his poetic voice again in mid-2018, following a period when he hadn’t been writing much of anything. He wrote three new pieces for the Colorado State Fair’s 2018 poetry contest, which he’d won in 2017.

“I don’t know where this is coming from, but I’m writing well right now,” he says. “It seems ironic because there’s so much that I can’t do. It just happens to be pleasing and, I think, successful.”

Topically, he’s acknowledged his illness and mortality. When the Indy spoke with him in 2012, ahead of his Business of Art Center (now Manitou Art Center) show titled for dying out loud, featuring coffee- and bleach-stained paper quilts covered in text, Taylor said “Americans… just do anything short of embalming themselves while their hearts still beat to evade the issue of death, and I see it everywhere.”

Mostly, however, he’s exploring contemporary subject matter.

“Ninety-eight percent of what I produce now has to do with fuckin’ Donald Trump,” he says. Like many, he watches Washington with the morbidity typically associated with rubberneckers slowing for a particularly nasty car crash. “Because I’m a writer, I want to be in tune with those little weird things that he does.”

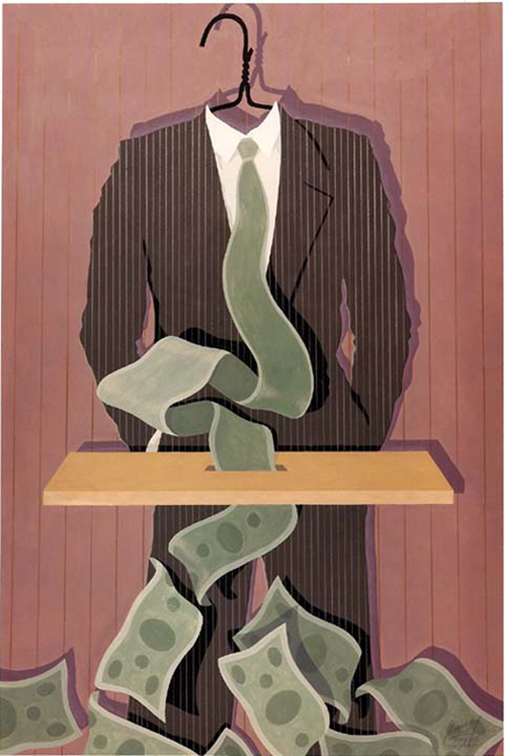

He’s always had an eye for the topical, and especially since he started writing, he’s been something of a firebrand. Gregory Howell — who hosted a 2017 retrospective show of Taylor’s work at Pueblo’s Kadoya Gallery and wrote a full retrospective of his career — recalls a heart-wrenching series of works Taylor did in response to the AIDS crisis. He used clothing, hangers and mannequin heads to construct a haunting and heartbreaking memorial to those who died.

“Spiel is not a shy guy,” says the Sangre’s Richerson. “We are fortunate that this gifted artist… calls the greater Pueblo area his home. His work most certainly enriches the local art scene.”

But if it can be said that Taylor’s made an impact on anyone, it’s on Welch. Over the last three years, he has been Taylor’s full-time caregiver.

“He tries to focus on his art and his writing,” says Welch. “And that takes all of his energy. So he doesn’t have a lot of energy left over for other things.”

So when Welch, 64, isn’t maintaining their garden with skills from a horticultural career, he’s cooking, cleaning, doing laundry and making sure Taylor takes care of himself. He hits moments of frustration, as anyone does. But it’s striking how well Welch keeps everything in perspective.

“It’s better than dying young, you know,” he says. “We could have been dead at age 40. Here we are in our 60s and 70s, both alive, and we try to be grateful for that.”

Taylor knows just how much Welch’s support has kept him going. A few years ago, he wrote a poem called “Leaving,” about the slow loss of his faculties. Its final stanza reads:

“When I know no equivalent of dusk nor dawn and / you no longer feel a need to visit me, on the day / I am unable to miss you, you will know for certain that / I’ve forever lost my song.”

THE PUEBLO CHIEFTAIN

OUTSIDE the LINES

Creativity helps Pueblo West poet-artist cope with life

Published: June 29, 2008

By SCOTT SMITH He’s a puzzle of a man. He is artist Tom Taylor. He is the poet Spiel. He is a world-weary soul with impassioned blue eyes, a wispy gray ponytail and a kaleidoscopic personality. He is intense and iconoclastic, creative and loquacious, intelligent and obsessive, engaging and cynical. He’s also mentally ill. “I have a hard time with life,” says Taylor, 67. “I am unusual. I’ve always been unusual. And I’ve always been aware that I was unusual. . . . It’s the truth. I’m strange.” Strange, yes. Successful, too, despite the battles that clatter around inside his head as Taylor wrestles with life’s everyday challenges. A Pueblo West resident for the past decade, Taylor is one of the area’s best-kept artistic secrets. Some of that is because few people here know him as Tom Taylor – in these parts, he’s known as Spiel, a poet with a penchant for darkness and discomfort – and some is because of his insular lifestyle. A typical day for Taylor – or Spiel, if you prefer – consists of work, work and more work in his home office, occasionally interrupted by a smoke break in his peaceful rooftop garden or some quality time with his dog, a sweet-and-feisty heeler named Gracie. He ponders. He writes. He edits. He polishes. And then he wakes up the next day, takes his 13 prescribed medications (for “multiple diagnoses” of mental illness and physical maladies that include fibromyalgia, cluster headaches and arthritis), and does it again. “He’s very dedicated to his work,” says Paul Welch, Taylor’s partner for the past 24 years. “When he was an artist, he was consumed by that, and as a poet, he’s consumed by his poetry. That’s probably the main motivation in his life.” Says Taylor, shaking his head, “I never dreamed that I’d stand up and say, ‘I am a poet. I am the poet Spiel.’ It’s astonishing to me.” He’s a prolific wordsmith, cranking out chapbooks (small books favored by small-press publishers) filled with sharp-edged poetry that ranges from searing to satirical and explores the cobwebbed corners of the human condition. The subjects are real and raw: incest, suicide, war, death, love. “I think life’s uncomfortable,” he says. “One of my therapists once said, ‘Sometimes I think you live in a war zone.’ And I said, ‘I do. Doesn’t everybody?’ . . . I think a lot of people wouldn’t admit it, but doesn’t everybody get up in the morning and sort of duck and cover?” Taylor’s perspective is hardly surprising for a man whose long, strange trip through life has been longer and stranger than most. “When I was 30 years old, I thought I’d be a famous artist. I thought I’d be comfortable and admired, like I’d be Matisse or something,” he says. “But it hasn’t turned out that way.”

The passion inside

At his peak, Taylor was a commercially successful wildlife artist who also produced critically acclaimed works laced with in-your-face social commentary. From 1964 to 1996, he had nearly 50 solo exhibitions in museums, galleries and private showings. His images appeared on needlepoint patterns, in magazines, on record album covers and book jackets – even on coffee mugs, serving trays and bedding sets in the case of his signature piece,”Tuskers,” a stylish, mesmerizing rendition of an elephant herd.

“Tuskers” (c) 1985 Tom Taylor Tuskers became a highly successful fine art poster for The Field Museum of Natural History leading then to interest in Taylor’s work by the World Wildlife Fund. Determined Productions, an international licensing agency, represented him and Tuskers became the most lucrative, royalty producing image of his career as a wildlife artist during the 80s, when he was best known for his elegant, hard-edged, gouache paintings of animals and birds.

“I don’t know where this is coming from, but I’m writing well right now,” he says. “It seems ironic, because there’s so much that I can’t do. It just happens to be pleasing and, I think, successful.”

Topically, he’s acknowledged his illness and mortality. When the Indy spoke with him in 2012, ahead of his Business of Art Center (now Manitou Art Center) show titled for dying out loud, featuring coffee- and bleach-stained paper quilts covered in text, Taylor said “Americans… just do anything short of embalming themselves while their hearts still beat to evade the issue of death, and I see it everywhere.”

Mostly, however, he’s exploring contemporary subject matter.

“Ninety-eight percent of what I produce now has to do with fuckin’ Donald Trump,” he says. Like many, he watches Washington with the morbidity typically associated with rubberneckers slowing for a particularly nasty car crash. “Because I’m a writer, I want to be in tune with those little weird things that he does.”

He’s always had an eye for the topical, and especially since he started writing, he’s been something of a firebrand. Gregory Howell — who hosted a 2017 retrospective show of Taylor’s work at Pueblo’s Kadoya Gallery and wrote a full retrospective of his career — recalls a heart-wrenching series of works Taylor did in response to the AIDS crisis. He used clothing, hangers and mannequin heads to construct a haunting and heartbreaking memorial to those who died.

“Spiel is not a shy guy,” says the Sangre’s Richerson. “We are fortunate that this gifted artist… calls the greater Pueblo area his home. His work most certainly enriches the local art scene.”

But if it can be said that Taylor’s made an impact on anyone, it’s on Welch. Over the last three years, he has been Taylor’s full-time caregiver.

“He tries to focus on his art and his writing,” says Welch. “And that takes all of his energy. So he doesn’t have a lot of energy left over for other things.”

So when Welch, 64, isn’t maintaining their garden with skills from a horticultural career, he’s cooking, cleaning, doing laundry and making sure Taylor takes care of himself. He hits moments of frustration, as anyone does. But it’s striking how well Welch keeps everything in perspective.

“It’s better than dying young, you know,” he says. “We could have been dead at age 40. Here we are in our 60s and 70s, both alive, and we try to be grateful for that.”

Taylor knows just how much Welch’s support has kept him going. A few years ago, he wrote a poem called “Leaving,” about the slow loss of his faculties. Its final stanza reads:

“When I know no equivalent of dusk nor dawn and / you no longer feel a need to visit me, on the day / I am unable to miss you, you will know for certain that / I’ve forever lost my song.”

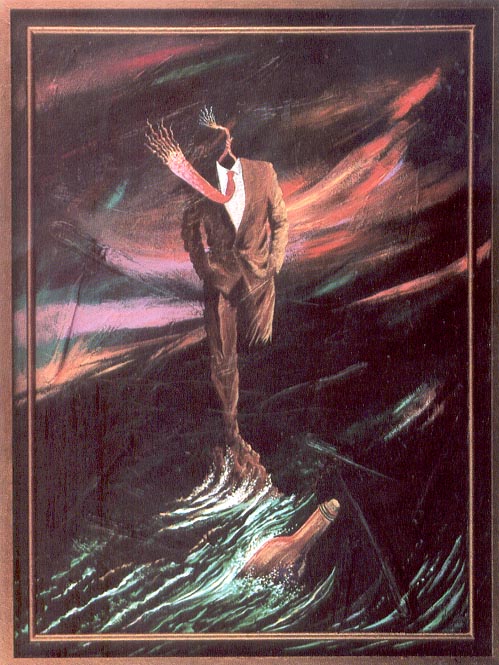

“Message In a Bottle” (c) 1985 Tom Taylor The futility of communication is a recurrent theme is Taylor’s work. Here, he sees himself as a one-legged man, stranded on stormy waters where he’s launched a plea in a bottle, knowing full well it is unlikely to reach a meaningful destination. Note the actual knives built into the surface of this painting. Note also the irony that this painting was done in the same year that he executed his landmark “Tuskers” painting. Characteristically, Taylor has juggled “commerce” and “gut” painting throughout his career.

He worked hard. He crashed hard. And just days after emerging from the hospital after fighting through a nervous breakdown in the mid-’80s, he met Welch in Denver. They’ve been together ever since – a complementary pairing of laid-back and intense. Taylor continued to crank out piece after piece. But he gradually became bored with the same old, hard-edged beasts on canvas, and he adopted a new style in the mid-’90s that used mixed-media and created “wilder” wild animals. It wasn’t well-received by a public expecting the Taylor look, though, and the artist became disheartened. And then Tom Taylor died.

Preparing to die

In the fall of 1996, Taylor was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. His doctor gave him six months to live. If there’s ever anything you and Paul have always wanted to do, she said, now is the time to do it. “Paul said that within 45 seconds, I gave up my career,” Taylor says. He sold off most of his inventory. The men traveled to Mexico, and to Yellowstone National Park. And Taylor waited for the end. “I decided that the best thing to do was to learn to love dying,” he says. “I used to lie in my bed and look up at the ceiling and say, ‘OK, OK, I’m ready.’ ” But a funny thing happened on the way to the afterlife: It turned out that Taylor didn’t have pancreatic cancer. His pancreas had wrapped itself around his common bile duct, producing similar pain and symptoms to the deadly cancer. But by the time the doctors figured that out, Taylor’s brain was dead-set on dying. “I couldn’t start to learn to love living,” he says. “I couldn’t get back.” Complicating matters, his pain persisted. Surgeons would insert a stent so his bile duct would drain and everything would be fine for a while, but then the blockage would return.They replaced the stent 17 times. Frustrated on all fronts, Taylor and Welch moved to Pueblo West in 1998. And shortly thereafter, Taylor underwent biliary bypass surgery in Colorado Springs – a procedure that finally solved the problem and stopped the pain. As he regained his strength, Taylor also redefined himself. He wrote short stories, and then poetry – and he metamorphosed into his current persona: The Poet Spiel. His imagination surged, and the written word became his new medium for personal expression. And the small-press publishers loved his lower-case, punctuation-free verse, which was filled with deep texture and genuine passion. “I didn’t really know what I was doing at first – I was just messing around,” he says. “But I sent some stuff off to a few places and immediately started getting accepted . . . and I’ve been on a roll ever since.”

A creative comeback

But even as his newly discovered creativity came tumbling forward via his written word, his feeling of incompleteness – so evident in his lifelong imagery of faceless and headless people, and houses without doors and windows – persisted. He still had no interest in picking up a paintbrush. However, that changed about a year ago. Inspired by an abstract exhibit at the Sangre de Cristo Arts and Conference Center – and by interest showed in his work by then-interim curator Trisha Fernandez – Taylor went back to the canvas. The plan was for him to produce some new paintings to go with his vast and varied collection of older pieces, and to couple them with his poetry in a 2009 exhibit at the arts center. It was a tantalizing prospect: a chance to pair Taylor and Spiel in a respected gallery. Slowly and painfully, Taylor went to work, producing five new paintings in his favorite medium, gouache. There was a faceless self-portrait, a piece showing a crowd of people with buttons for mouths, and an intense work that included an American flag, barbed wire, a baby factory, a row of dodo birds, flying harpies and the words “Jesus Hates Dead Babys(sic).” Just as importantly, he was able to maintain his poetry career at the same time. “At that point, I started to be alive again,” he says. “Something gave me the confidence to unite those two pieces of me into one for the first time since I died.” But his elation turned to despair last winter. The show was canceled because of a contractual disagreement between Taylor and the arts center’s executive director, Maggie Divelbiss.Taylor, ever in tenuous balance with himself, was devastated. “I have not painted since,” he says. Perhaps what bothers Taylor the most is that the lost show was a chance to make a profound statement about what mentally ill people can accomplish. “It was to be a public expression to encourage others,” he says. “It was going to say: Look at me. Tomorrow you can get up and be an abstract artist, and the next morning you can be a realistic artist, and the next morning you can get up and be a writer, and the next morning you can get up and write a novel, and the next morning you can get up and write poetry. And you can do it out loud and you can do it in private, and you can fingerpaint and you can scribble on the floor. “You can do all those things and don’t let anyone say you can’t. . . . I’m living proof. But it ain’t been easy.” For now, Tom Taylor and Spiel are separate again. But somewhere deep within his synapses, Taylor knows that his inner artist and poet are no longer mutually exclusive. “It’s like my shrink tells me: ‘You made that leap of faith. You made that step,’ ” he says. So where does Taylor go from here? He can’t tell you for sure, other than to say he’s working hard on two new poetry books (one is “Once Upon a Farmboy”), has recorded a spoken-word CD and expends much energy dealing with his daily pains. “I’m not looking for a show. I’m not out there knocking on doors. And I’m not just an artist,” he says. 6/08